The cycle of encounters “Inclusive Urban Metaverses” held in Kaunas (Lithuania) was the first ever occasion where the topic of the metaverse was approached under a social justice lens in the framework of an urban regeneration project. It emerged how digital land could be a space to extend the right to the city and not just a digital twin for top-down modelling. The full report is available here.

The context

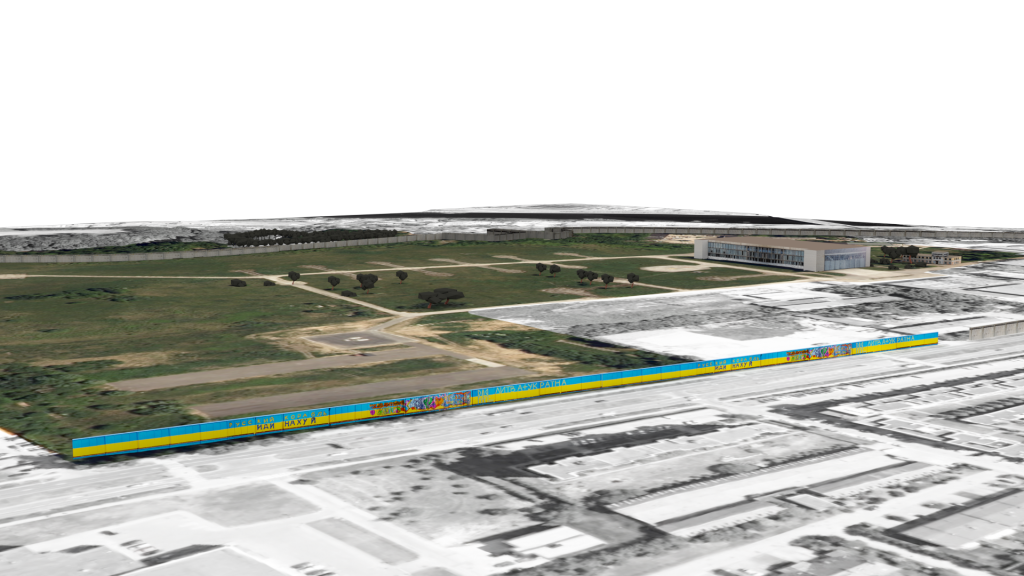

In 2022 I curated the “Inclusive Urban Metaverses” series to explore how the collective and inclusive elaboration of novel digital territories twinning urban regeneration areas can support placemaking. The context sees the transformation of a former military helicopter factory site into an innovation park. In the regeneration process, local partners Kaunas Design Library and Kaunas Technology University are challenged with transitioning the area’s identity from a soviet military connotation to an ‘innovation sandbox’ while activating participatory processes that allow citizens to appropriate and transform the site’s legacy, identity and physical space. My intervention to support the process was held in the framework of the T-Factor project, which develops new knowledge, tools and approaches to temporary urbanism that can contribute to inclusive and thriving futures in cities. Since the area presents a variety of legal and infrastructural constraints for exercising established temporary urbanism tactics, we looked into digital placemaking (utilising digital technology to foster deeper relationships between people and places) as means to provide a viable meanwhile strategy for engagement and sensemaking.

From the “smart” to the “extended” city

The curatorial choice was to address the emerging field of city-related metaverses under a social justice lens, working both on a design and policymaking level with international experts (which requirements would make an urban metaverse more inclusive? How can such digital lands serve the public interest?) and a bottom-up one by designing with citizens thematic districts of the digital land. A manifesto gave the initial direction to the work and identified societal challenges associated with the development of metaverses:

“The mental models of the metaverse reiterate those of big tech and their social externalities: the financialisation of every walk of life (associating identities and tokens, forcing in-platform shopping to enjoy a full experience); the top-down design, in the hands of a not-very-diverse elite of experts (underserving women, queer individuals and POC, generating sexual abuse and ignoring how to protect minors in virtual environments) and anthropocentrism (environmental concerns have not yet reached these platforms relying on high computing power, new hardware and fast networks).”

Conclusions

The encounters with international experts gave life to inclusive design principles that consider technology requirements and social equity. The activities with citizens showed how the AIIP metaverse could accelerate social and cultural change. Indeed, this anticipatory space could embody solutions that individuals seek, but that are hard to materialise collectively for historical and cultural reasons. For instance, in the case study of Kaunas, there is a demand from individuals affected by specific diseases for holistic care. Still, this approach struggles to emerge in local medical culture. Having a place for community building and experimentation around immersive non-traditional care journeys would support sufferers, connect them with well-established practices and practitioners, and innovate the city’s health offering.

Final recommendations

The cycle’s final outcome is a double set of recommendations for urban regeneration processes and general city-making.

1) The participatory elaboration of a metaverse layer in urban regeneration processes can add value as follows:

Free the imagination of participants to think of outcomes that are considered inconceivable within built-world constraints.

Federate community around what is considered a safe space, a neutral area to start dialogues that it would be hard to put in place in the building of a project with more constraints.

Create an extra layer of identity and meaning for the urban regeneration area. Provide inputs for other “traditional” activities via the ideation and community-building process.

Develop a community-based use case that can be proposed to metaverse developers when times are mature: the more the use cases that are based on real needs and expectations, the less urban metaverses will slip into dystopia.

2) Our early recommendations for any stakeholders interested in deploying urban metaverses with the compass of social justice include the following:

Build a feedback loop with reality: creating an escapist parallel world has little social impact and will only deepen social fractures. Consider the platform a place to speed up change and prototype a different kind of social aggregation, knowledge sharing and capacity building that can impact existing initiatives, for instance, via community building, fundraising, new policy topics.

Learn the lessons from urban regeneration best practices, including: understanding the perspective and expectations of the stakeholders involved, detecting real-world problems, having an inclusive approach, focusing on capacity-building.

Think in terms of extending the right to the city: consider which social groups struggle to exert fundamental rights in the city and how their needs could be supported with less initial friction in this new environment.

Centre problems that are hard to solve in the physical world: by detecting pain points of citizens, it is possible to federate a motivated community of co-designers and participants.

Refrain from falling into the imaginary crisis: think of how you can extend possibilities instead of simply reproducing digitally the existent city. This also includes having a critical view of technology and making sure that the means are adapted to the purpose.

Set strong social requirements for technology: ensure that privacy, trust and safety are inherent in the platform.

Overcome ableism and linguistic barriers: in virtue of its simulation potential, the metaverse can make accessible to everybody experiences that are not in the built world.